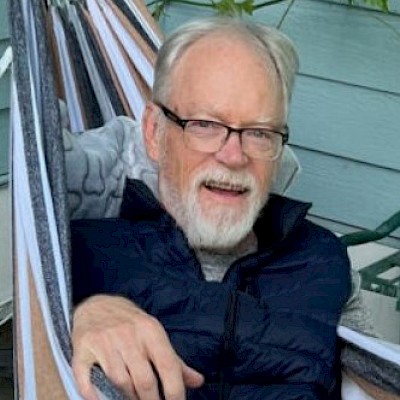

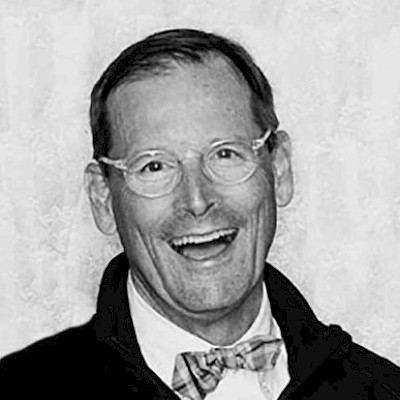

The Reverend H. Kris Ronnow died Friday, Oct. 25, from complications of Parkinson’s disease. He was 87.

A devoted husband, loving father and grandfather, Kris dedicated his life to the fight for social and economic justice. As a community organizer on Chicago’s West Side in the 1960s, architect of Oak Park, IL.’s blueprint for racial justice and diversity in the 1970s, and a leader in corporate reinvestment and philanthropic efforts in Chicago’s neighborhoods, he sought community-led solutions to complex problems.

Kris was “that rare combination of ordained clergy who lived his ministry within secular institutions,” his friend and colleague Rev. David Bebb Jones said, with a “prophetic sense of care and concern for all persons.”

The grandson of Danish immigrants, Henry Kristian Frederick Ronnow was born on July 4, 1937, in St. Paul, MN. His father Henry was a brick mason, a strong union guy. Mom Gladys was a homemaker. He had two older sisters, Joan and Nancy.

Kris attended Saint Paul public schools, graduating from Central High School in 1955. He was an active member of Saint Paul’s YMCA and De Molay, sang in the church choir and played (not well) the trumpet.

The first in his family to earn a college degree, he graduated from Macalester College in 1959 with a major in economics. That fall, he began graduate studies at both McCormick Theological Seminary and the University of Illinois in Chicago.

He married Constance Cory Youngberg on May 28, 1960, in St. Paul. Their first daughter Karin was born in 1962, at the Chicago hospital where Connie was a nurse, followed by Heather in 1963, and Erika in 1967.

Inspired by Saul Alinsky, his professor and friend, who penned “Rules for Radicals,” Kris did his graduate-level field work in some of Chicago’s most neglected West Side neighborhoods. In 1963, he completed his master’s degrees in divinity and social work.

He was a community organizer for the Church Federation of Greater Chicago (1963-1966) and executive director of the Interreligious Council of Urban Affairs (1966-1969), before joining the Presbyterian Church USA’s Board of National Missions in New York (1969-1972). Upon returning to the Midwest, he was director of Oak Park’s then-new Community Relations Department amid a difficult period of racial integration (1972-1977); vice president of public affairs at Harris Trust and Savings Bank of Chicago (1977-1988); and then full circle back to McCormick Seminary as vice president for finance and operations (1988-1996). He retired in 1996.

Kris often caught his adversaries off guard with his clear, well-informed well-reasoned arguments that they do right by people. He spoke truth to power. He demanded accountability. He could be very persuasive.

At his high school reunion in 1965, the principal pulled Kris aside “What on earth are you doing down there in Chicago?” Turned out, the FBI’s notorious Red Squad had been following Kris, building a file, and apparently thought (wrongly) this principal might have something juicy to contribute. Truth was, Kris had no intention of inciting a violent insurrection, or whatever the FBI worried about in those heady days. His goal was that all people be treated with dignity and given equal opportunity to thrive. Radical? Yes, but nonviolent to the core.

Amid racial strife in Oak Park, Kris worked tirelessly with grassroots groups to overturn racist and inequitable (and eventually illegal) real estate, bank-lending and employment practices. Bigotry and prejudice periodically followed Kris home, prompting a need for police protection. Oak Park’s leaders had his back.

The department “acquired the reputation as one of the most capable and progressive (community) relations departments in the country,” one local newspaper reported, and Oak Park remains a successful archetype for communities undergoing racial change. Kris’ work in Oak Park was, Jones said, “a most creative and long-lasting ministry.”

At Harris, Kris designed and managed the bank’s new foundation; counseled senior management on community engagement and reinvestment; and demonstrated the importance of engaging and rewarding employees. In so doing, he unwittingly became a sort of corporate conscience at the bank. In the late 1980s, as battles to end apartheid in South Africa escalated, he walked into then-bank president Stanley Harris’ office and boldly declared that the bank must stop buying and selling Krugerrand. Harris agreed. “Done.”

Kris served on numerous nonprofit organizations’ boards, including the National Conference for Community and Justice, the Center for Neighborhood Technology and the Center for Ethics and Corporate Responsibility. He was a teaching elder in Chicago Presbytery, often consulted for guidance on significant decisions, and helped small, struggling urban congregations rebuild. As active Macalester alumni, he and Connie endowed a scholarship program for first-generation college students from the Twin Cities.

Kris was a voracious reader – news, fiction, religious philosophy, history – and a lifelong learner who, with Connie, traveled the world, seeking new perspectives and a deeper grasp of complex issues. After an eye-opening trip to the Middle East in the 1990s, they joined Chicago-area efforts to help Palestinians resecure a piece of their homeland. They were “a unique couple, always on the cutting edge of issues,” Jones said.

In the 1970s, they bought a cabin in Green Lake, WI. An amateur sailor, Kris bought a boat and christened it “Attitude Adjustment.” “Sailing gave me time to reflect, reject worn-out negative thoughts, recalibrate, reposition and be renewed,” he said.

He loved folk songs and hymns, organ music, brass bands and symphonies, and the sound of many diverse voices singing in unison – loudly.

He was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2007. Five years later, he and Connie moved to Westminster Place in Evanston, a Presbyterian Home with the continuum of care they knew they’d eventually need. Soon he was organizing there, too, advocating for residents seeking transparency from the administration as chairman of the Residents Council.

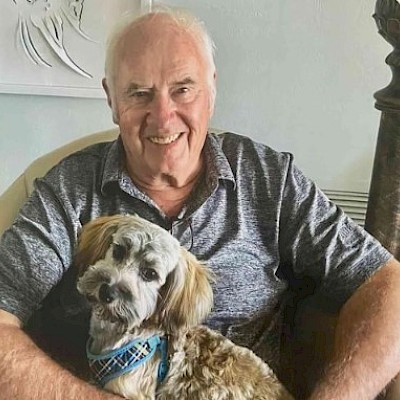

Kris worked hard to slow Parkinson’s inevitable progression. He knew he had to “move it or lose it.” He’d always had a dog, so long walks were routine, and workouts at the gym became another habit. When his balance inevitably deteriorated and reaction time slowed, he donated his boat to a sailing school and he and Connie sold the Green Lake house.

“The old green canoe is not too stable,” he wrote. “I cannot get into the kayak. The sailboat is too fast. And I have not figured out how to walk on water.”

Kris was preceded in death by his parents Henry (1904-1965) and Gladys (1906-1978); and sisters Joan Willaman (1931-2015) and Nancy Cooper (1934-2022).

He is survived by his wife, Constance Cory Ronnow of Evanston, IL; daughters Karin Ronnow (Kim Leighton) of Livingston, MT., Heather Ronnow (Rick Kozal) of Elgin, IL., and Erika Ronnow of St. Paul, MN; granddaughter Carmine Abigail of Belfast, Maine; grandson Colter Kozal of Pasadena, CA.; seven beloved nieces and nephews; and countless friends and admirers.