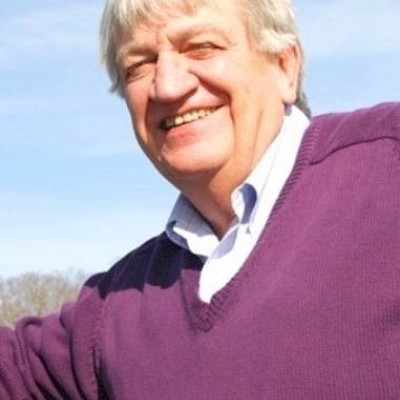

John Samuel Johnston, Jr., also known as Sam, Poppa or Judge, surrounded by family, died December 10th from complications of Parkinson's disease which he battled for over 22 years. He was predeceased by his parents, John Samuel Johnston and Ruth Richards Johnston, and a son, Adam Wood Johnston (in 1977). He was married to the love of his life, Elizabeth Whitaker Thomasson Johnston, for over 54 glorious years.

He was a judge in the 24th circuit for over 31 years. He was 30 years old when first appointed to General District Court in 1977, the youngest district judge at that time in Virginia. Four years later he was elevated to circuit court and, at 34, was the youngest circuit judge in Virginia.

He was born November 29, 1946 in Anniston, Alabama and was raised in Weaver, Alabama. He received his education in the Alabama school system and was a graduate of the University of Alabama in 1968, where he was a member of Chi Phi social fraternity. He was a diehard fan of Alabama football and had many wonderful years watching the TIDE ROLL.

After the University of Alabama, he took his law degree at The University of Virginia, graduating in 1972. He was a member of Phi Alpha Delta legal fraternity and was elected to the law school council as a third-year student. After graduation, he began a one-year judicial clerkship in Birmingham with chief federal Judge Frank McFadden of the northern district of Alabama. After his clerkship, he returned to Lynchburg and began practicing law with Kizer, Phillips & Petty where he worked for 3 ½ years before being named judge.

He is survived by his wife, daughter, Margaret Richards Johnston Shoemaker (Jason); son, Whitaker Rustel Johnston (Abbey); daughter, Mollie Gleason Johnston Hollingsworth (Mark); daughter, Annie Gordon Johnston Vordermark (Matt); and bonus daughter, Elizabeth Page Pettyjohn Birney. He also is survived by grandchildren, Caroline Elizabeth Shoemaker, Thomas Adam Shoemaker, Samuel Robert Johnston, Scarlett Richards Johnston, Margaret Howard Vordermark, Frank Rustel Vordermark, and Kendall Mae Ramsay Hollingsworth.

Sam was an engaging, garrulous person who was at ease with everyone. He became friends with several individuals whom he had previously sentenced to the penitentiary and occasionally had lunch with them. He was a true sesquipedalian and a bibliophile - completing at least two crossword puzzles each day and attempting to add a new word to his vocabulary every day as well.

Sam was blessed with a keen intellect and a wonderful sense of humor – always looking forward to telling or hearing a good joke, whether told by him or someone else; he must have had at least 1000 jokes stored in his brain! It was not unusual for him to introduce Liz as his "first wife" or "current wife" or the "incumbent" wife all the while knowing how important she was to him.

Having loved several dogs throughout his life, his dog Dixie – a yellow lab – was his favorite. She hunted doves with him for many years. Sam loved the outdoors, especially dove shooting and he regularly would arrange dove hunts on farmland in Campbell and many other surrounding counties. He had a group of friends who would go with him and his son on many Saturdays and loved the camaraderie, especially with his son and daughter-in-law and daughter and son-in-law and his hunting buddies too numerous to name. He successfully participated in dove hunts as recently as September of this year. Sam was well known for his wild game dinners at the end of each hunting season which featured exotic meats such as moose, yak, cobra, mountain lion, bear, ostrich, emu and alligator. He belonged to 4 chitterling clubs: Blue Ridge; Central Virginia; Seminole Trail; and Tobacco Row.

Sam was an avid gardener, planting as many as 30 tomato plants along with rows of corn, green beans, squash, cucumbers, eggplant and okra (his favorite vegetable). He once grew an 8 lb. 3 oz. sweet potato. One year he won a ribbon at the Campbell County Food Fair for his Zucchini Relish. Sam spent many long and happy hours in the garden and shared his harvest with friends, neighbors, and family.

Sam also loved to teach. After graduating from Alabama he taught at the junior high in Scottsville, high school at Rock Hill Academy in Charlottesville and at Central Va. Community College and Averett College. He regularly went to the local schools to speak to government classes and welcomed high school students to attend trials of interest.

Having served for 31 years, Sam had special insight to the problems society brought to him. He was known as a fast, fair, and patient judge with a great sense of humor and acquitted himself thusly throughout his tenure. He served on Governor Robb's task force to combat drunk driving and Governor Wilder's commission for parole and sentencing reform and was a charter member of the Virginia Sentencing Commission.

He was a popular representative of the judiciary and was frequently asked to speak or present to various civic organizations and bar groups over the years. Among them were the Va. Bar Assn (VBA), the Va. State Bar (VSB), the Va. Assn of Defense Attorneys (VADA) and the Va. Trial Lawyers Assn (VTLA). He led the VTLA judges panel at its annual convention for 16 consecutive years and was awarded the VTLA Distinguished Service Award in 2007. Sam was also a guest presenter, lecturer, and instructor to groups and bar associations across the country. During his career and travels he became friends with noted authors Mickey Spillane (creator of Mike Hammer) and Lewis Grizzard (noted Southern humorist), and Bobby Lee Cook (the Georgia attorney who inspired the Matlock series).

He is the author of "Why Judges Wear Robes" and co-author of "The Art and Science of Mastering the Jury Trial" with Irv Cantor. He was named a Leader in the Law in 2011 and in 2016 received the Champion of Justice Award from the Va. chapter of the American Board of Trial Advocacy given to a judge "for his service to the community and for exemplary contributions to the people of Va." For many years Sam invited jurors to return to court for a debriefing and question and answer session. He often told the jurors he did not want to treat them like mushrooms, i.e. "keep them in the dark and feed them horse manure". Sam was one of the founding members of Juridical Solutions, a mediation group of retired judges across the state. Sam was honored to sit as a judge in Campbell County and considered Rustburg to be a second home. One of his landmark accomplishments was the construction of the new courthouse there to serve those who needed to be heard or were seeking justice.

Sam loved going to Litchfield Beach, S.C. with his family for over 40 consecutive years. But the thing he loved most was being with his family – Liz, Margo, Whit, Mollie Gleason and Annie Gordon; his sons-and-daughter-in-law; and his 7 grandchildren. Poppa was a hands-on father and never missed a baseball, softball, or soccer game in which one or more of his children participated. He also made it to every piano and dance recital to support his children in their activities.

The family truly appreciates each and every one who cared about him and helped him when Parkinson's was attacking his ability to care for himself. The family is especially grateful to faithful friend Joe Malott, the local Parkinson's Disease Support Group, Rock Steady Boxing, Centra Hospice, and to Candy, Erica, Peggy and Towanda.